Empoisonnez-vous avec la médecine traditionnelle chinoise.

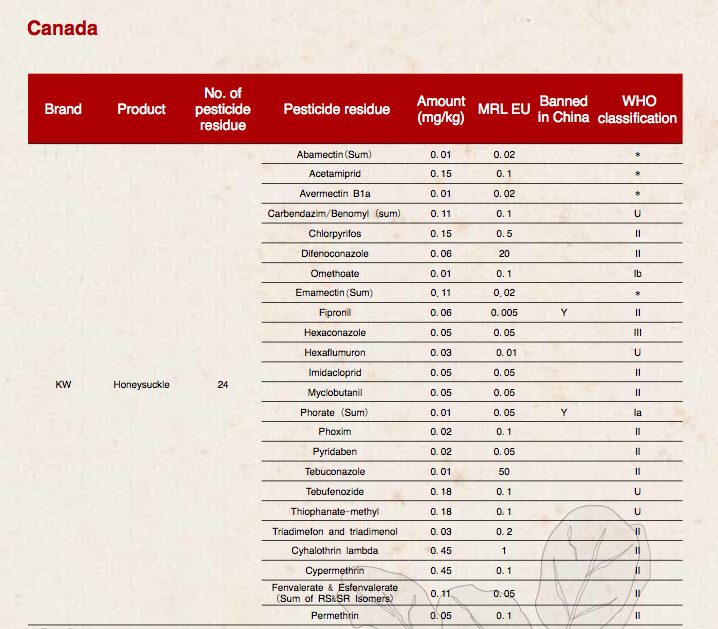

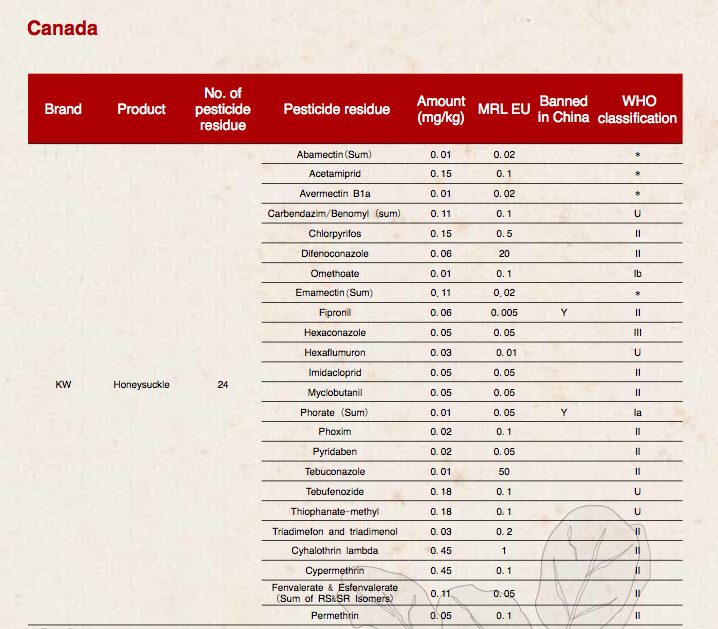

[24 pesticides différents dans un échantillon de chèvrefeuille acheté au Canada.]

Greenpeace, Eric Darier: “Pesticides: the secret ingredient in Chinese herbal products?”

Est-ce que Santé Canada — qui n’a pas encore pris connaissance de l’enquête de Greenpeace, dévoilée aujourd’hui au Canada — teste les herbes chinoises ? « On a effectué des analyses sur un petit nombre de remèdes traditionnels chinois au cours des cinq dernières années afin d’y déceler la présence de résidus de pesticides, et aucun résidu de ce genre n’a été trouvé », a répondu Leslie Meerburg, porte-parole de Santé Canada.

La Presse.

Le budget de l’Agence canadienne d’inspection des aliments a été amputé de 56 millions de dollars par le gouvernement Harper.

Au Québec, sans pratiquer la médecine chinoise, vous vous méfierez aussi de l’ail, du jus de pomme (et tout cocktail de jus de fruits en contenant probablement, ex. Oasis), des légumes surgelés (ex. Arctic Gardens), des poissons et crustacés surgelés, du miel, des champignons en conserve ou déshydratés, des yoghourts aux fruits (ex. Danone), du gingembre, des pois mange-tout, des carottes, des fraises, des mandarines, des poires, des pomelos, des litchis, etc.

Contrairement aux pays européens, soucieux de qualité alimentaire, il n’est pas obligatoire au Canada d’indiquer la provenance de nombreux aliments. Seuls les noms des importateurs et/ou transformateurs doivent figurer. Le Québec importe annuellement pour 170 millions de dollars d’aliments chinois.

Les femmes japonaises mettent le holà aux beuveries hedomadaires de leurs maris, par économie.

For Japanese men, the budget for a Friday night out on the town has nothing to do with how much they earn. What matters is how much your wife gives you—and the bad news is that it’s not as much as it used to be.

In at least half of Japanese married households, the wife controls the budget and allocates a proportion of her husband’s salary for spending money known as “okozukai”—which covers mobile phone bills, drinks, cigarettes, and entertainment. The average allowance has slipped to $386 per month, according to a new survey by Shinsei Bank (pdf), down 3% from last year and to the lowest level since 1982.

Last year the BBC interviewed one 47-year-old Japanese man who had been receiving an unchanged allowance from his wife for 15 years. He tried to negotiate a raise, but “she [drew] a pie chart of our household budget to explain why I cannot get more pocket money,” he said, defeated. […]

Quartz, Jake Maxwell Watts: “Japanese husbands get allowances—and they’re at a 31-year low, in a bad sign for Abenomics”.

L’okuzai est converti en hesokurigane :

[…] This situation is partly the reason for the flipside of okozukai: hesokuri-gane, which means “money hidden in the navel,” and usually shortened to just hesokuri. Westerners might call it “pin money.” It is cash that housewives regularly stash away without telling their husbands. In the popular imagination it has two very different purposes. On the more noble side it is money that wives — keepers of the purse — maintain for emergencies or old age. On the less noble side it is a fund they maintain for themselves, to go out for lunch with their girlfriends or to buy something for themselves since stereotypically Japanese husbands rarely purchase gifts for their wives. A survey carried out by Yomiuri Online last year found that the amounts of hesokuri saved by respondents varied from ¥1.5 million to ¥40 million. In most cases the fund was accumulated after the wedding, but a few women confessed to having saved money on their own before getting married and not telling their husbands about it. “My husband has a tendency to get into debt,” one woman who had been married 20 years said in the comments section. “So I save money just in case I have to run away from him.”

For the simple reason that hesokuri is, by definition, “secret” (in another 2010 survey by the life insurer Sonpo Japan DIY, 45 percent of wives said they have money their husbands don’t know about) it can be seen as a corrective to family laws that favor husbands. As mentioned above, the Civil Code forbids joint bank accounts, and so housewives without incomes of their own usually have to draw household expenses from their husband’s account. And while titles to property can include both names of a married couple, the party who is not responsible for the loan–usually the wife–must explain where the money she is contributing to the property comes from. Many foreigners are baffled by Japanese divorces in that a woman who seeks a split usually comes away with nothing, even after decades of marriage. That’s because the idea of joint property is, in a legal sense, non-existent. If the husband is the one making the money, that money always belongs to him, so technically hesokuri is illegal since it could be interpreted as a form of stealing. However, the Civil Code also stipulates that there is no such thing as theft within a family unit. The paradox is instructive, if a bit confusing. […]

The Japan Times, Yen For Living, Philip Brasor and Masako Tsubuku, July 5th, 2011: “Okozukai vs. hesokuri: An alternate view of home economics.”

Mauricio

Ca donne pas envie d’aller visiter :-\

Blah ? Touitter !